By Anusha Runganaikaloo

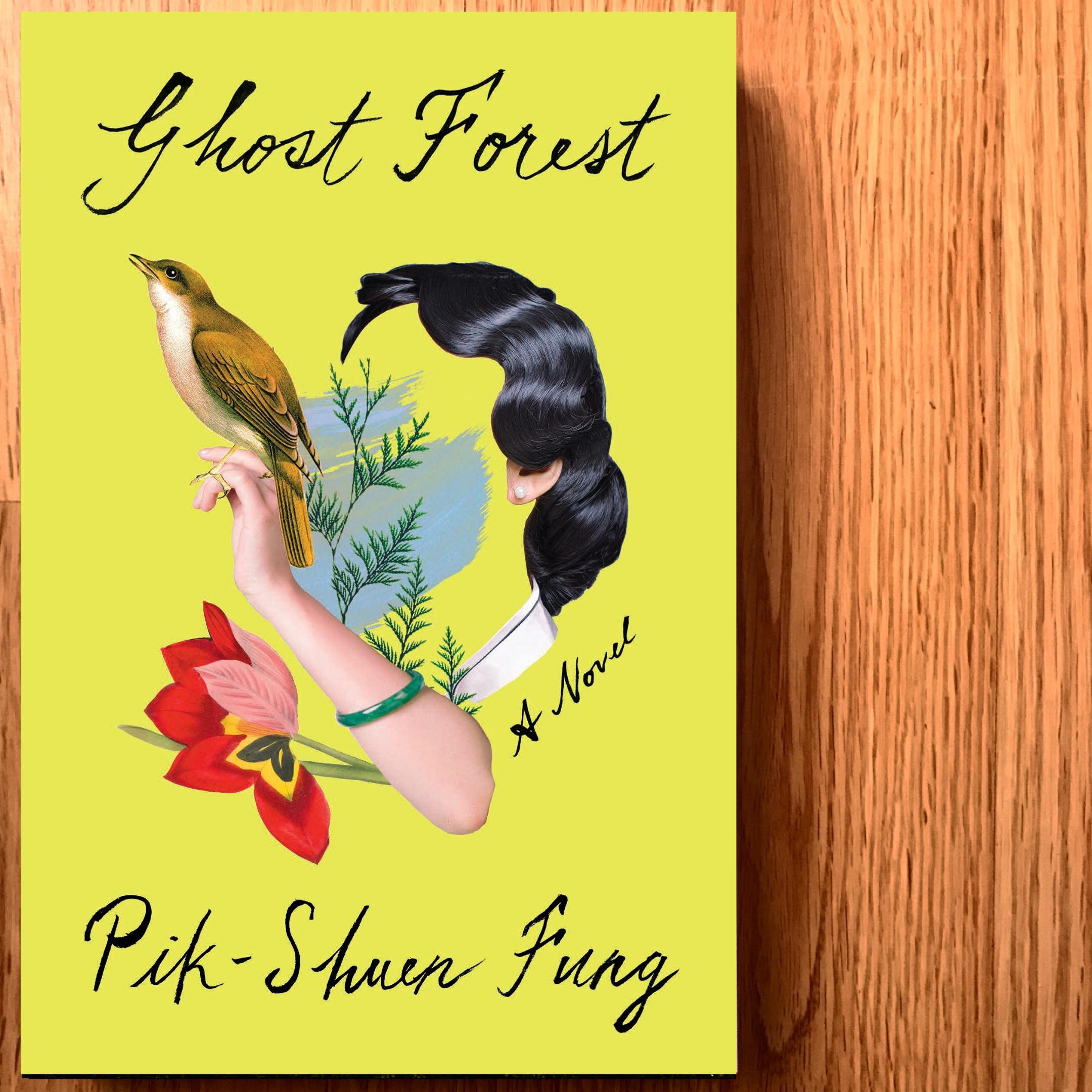

Pik-Shuen Fung’s debut novel Ghost Forest tells the story of a Chinese Canadian “astronaut” family: the protagonist’s father stayed behind to work, while the rest of her family immigrated to Vancouver in 1997, just before sovereignty over Hong Kong was returned to China.

The novel alternates between three different viewpoints: the narrator’s, her mother’s, and her grandmother’s. Each chapter, no more than a few pages long, describes a defining moment in the life of one of the three characters, not necessarily in chronological order, but rather as a standalone anecdote that often ends with an aphorism. These episodes, by turns funny, sad or philosophical, form a tapestry that depicts the interwoven destinies of three generations of women. Those destinies are different and yet strangely similar: the narrator’s grandmother, born to a poverty-stricken Chinese family in the 1930s, attends school only for one year but still manages to write an opera in exquisite calligraphy—and to star in it. She passes this creativity and vitality down to her daughter and granddaughters, and we witness with fascination how each generation paves the way for the next, to finally move together halfway across the world, carrying a wealth of centuries-old customs, wisdom, and knowledge.

Growing up in Vancouver, the narrator and her younger sister are caught between these traditions—transmitted to them through wise words, rituals, and prayers—and the values of their new homeland. The cultural gap becomes all the more obvious when their father falls sick back in Hong Kong. During this pivotal moment in the family’s life, the narrator summons various memories involving herself and her father. All these memories have one thing in common: they are characterized by misunderstandings and things left unsaid.

In a context where hard work and providing for one’s family are the ultimate proofs of love, and where feelings are hardly ever expressed in words, the young woman devises a successful plan to say “I love you” to her father for the first time…and to trap him into saying the words back, which is no mean feat.

The author, a visual artist, has conceived her book much like a sketchbook full of graceful vignettes. In one chapter, she explains the technique of ink bamboo painting, which she is learning at the China Academy of Arts, and where large areas of the paper are left blank because empty space is as important as form, absence as important as presence. What is crucial is to capture the artist’s spirit. These empty spaces where each story keeps on unfolding quietly, protected from our curious gazes, long after we have finished reading, are what makes this book so appealing. Where we would usually consider empty spaces to be a waste, we can almost picture the author sketching poetic, fragile characters surrounded by white. The white becomes part of the painting, breathes life into each character’s story, and gives space to every precious word, even—or especially—to the last ones whispered before a soul flies away. A haunting read!

Thank you, Penguin Random House Canada, for the complimentary copy in exchange for an honest review!