By Meredith Grace Thompson

Mussolini or Bacon?

He is fundamentally a colourist, in the childish sense. He draws simple pictures and he colours them in.

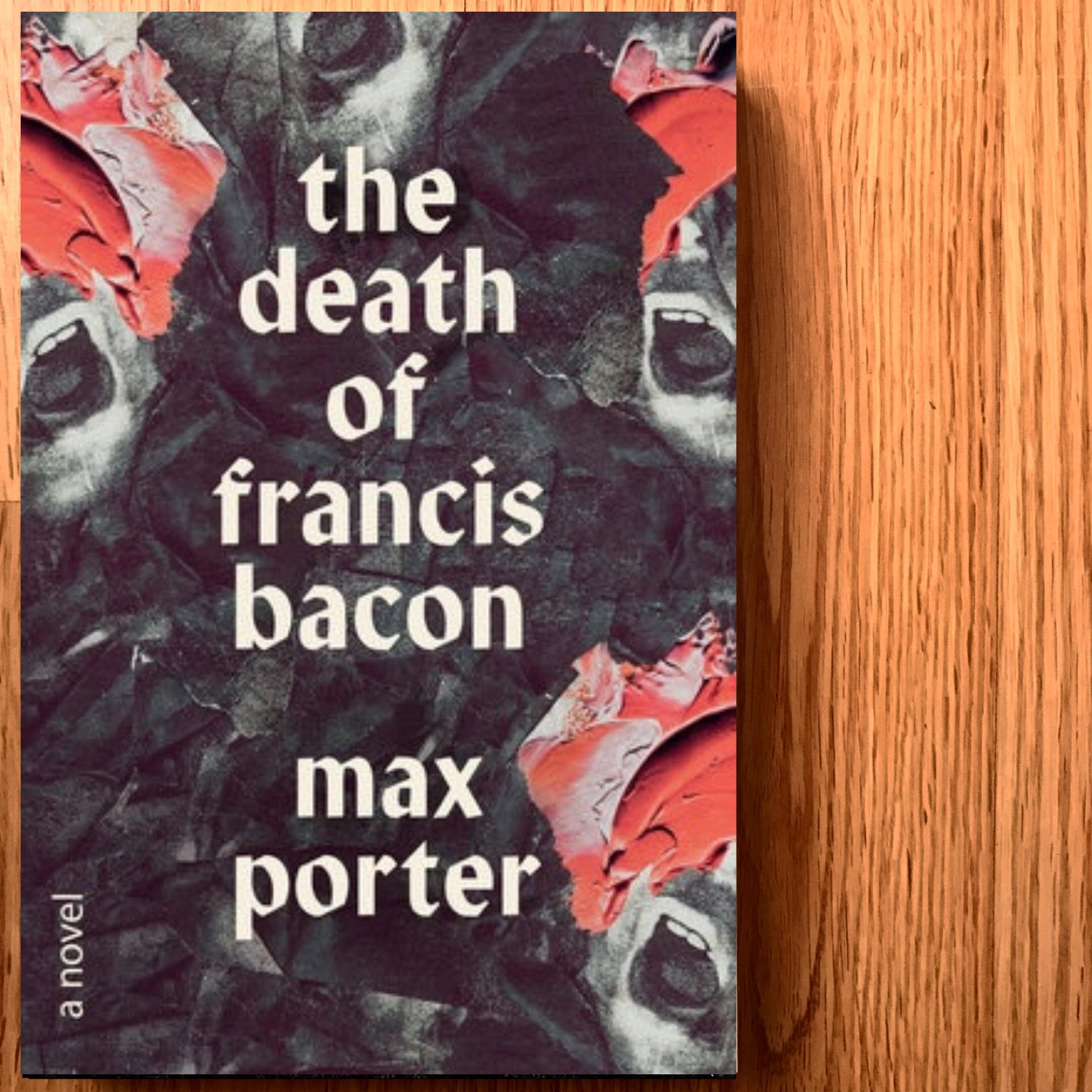

Max Porter is a strange and wonderful writer. His novels are quick and sprawling. Fast moving and yet in a near-permanent standstill of philosophising, each novel exists in the back of the reader’s mind long after it has been put down. He has a gift for capturing the immediacy of poetry in the larger narrative format of a novel, even if relatively speaking, his novels are short. Without his distinct self-declaration and identification of this work as novel, The Death of Francis Bacon could be labeled purely as experimental, climbing, ardent, grim, needful poetry.

Living inside the moments of the 1992 death of Irish-born painter Francis Bacon, Porter luxuriates in the strains of human consciousness without stepping into the cliché of a “life flashing before one’s eyes.” His words peak and fall, disintegrate and rebuild themselves as a human heartbeat, as human brainwaves. As much a comment on the speaker’s own obsession with Bacon—both as subject and as artist—Porter’s narrative voice floats evenly throughout the world of the novel. Moving from the speaker to Bacon himself without explanation or handholding, Porter creates an amalgamated self: a self inside itself, undifferentiable between writer and subject, speaker and spoken.

Playing with the implicit assumption of his subject’s namesake, Porter moves as effortlessly as human thought through taxi cabs and marital fights and lost cigarettes. Each section is differentiated by sequential numbering as well as the material and dimensions of the painting which follows, rather than chapter titles. Porter writes through each painting, creating each poetic prose piece as a potentially painted poem inside the larger context of a novel. These are paintings. These are colourings-in. These are movements within the strand which connects the multiplicity of selves. Porter’s speaker is reaching out to Bacon and Bacon is radiating towards the speaker.

This structure is Porter’s strength and is consistent throughout several of his novels. He does not seem to judge himself as a writer, rather takes that which he understands or seeks to understand and allows himself to climb through and over and under it. He looks at it from all angles. He holds it close and pushes it away. He is remarkably free in his writing.

Porter excels at using the art of others to better understand and create his own art. The paintings of Francis Bacon are grotesque and layered, their colours bright and unknowable. They sit inside the mind, reaching out towards you without hesitation. They are images of popes and kings, portraits beyond all else. They are stark and frightening, and if you look at the paintings only after reading this book, they will click into place as that which Porter has created—not models but rather interpretive dances. Porter is a weaver of images, a reader, an art historian, a lover of creation more than anything else. His book is a love letter, a disintegration of love, a recognition of love: the reception of a genius in ingenious terms. Porter manages to capture the moment of no longer knowing, the breakdown of human thought. The painting that is left behind. And after it all intenta descansar. Try to get some rest.

Thank you to Penguin Random House Canada for the complimentary copy in exchange for an honest review.