by Dahl Botterill

I was traveling with my family when I was first introduced to Frank Herbert's Dune. I had already read all of the books I'd brought with me and there were a couple weeks of touring left to occur, so we stopped at a used bookstore alongside a highway, somewhere long past remembering at this point.

I suspect most people learn of Dune when they are told that Dune is a must-read, that it's among the greatest science fiction novels ever written, that they can't truly claim to be a fan of science fiction while leaving that stone unturned. A close friend or fellow fan, perhaps a favourite critic, sharing their love of this incredible tome. Myself? I was browsing this long low building in the general vicinity of nothing, independently scanning shelves filled with books while my family did the same, when my mother stepped up behind me and drew Dune from the shelf in front of me. "You might like this," she said, handing it to me, and that was that.

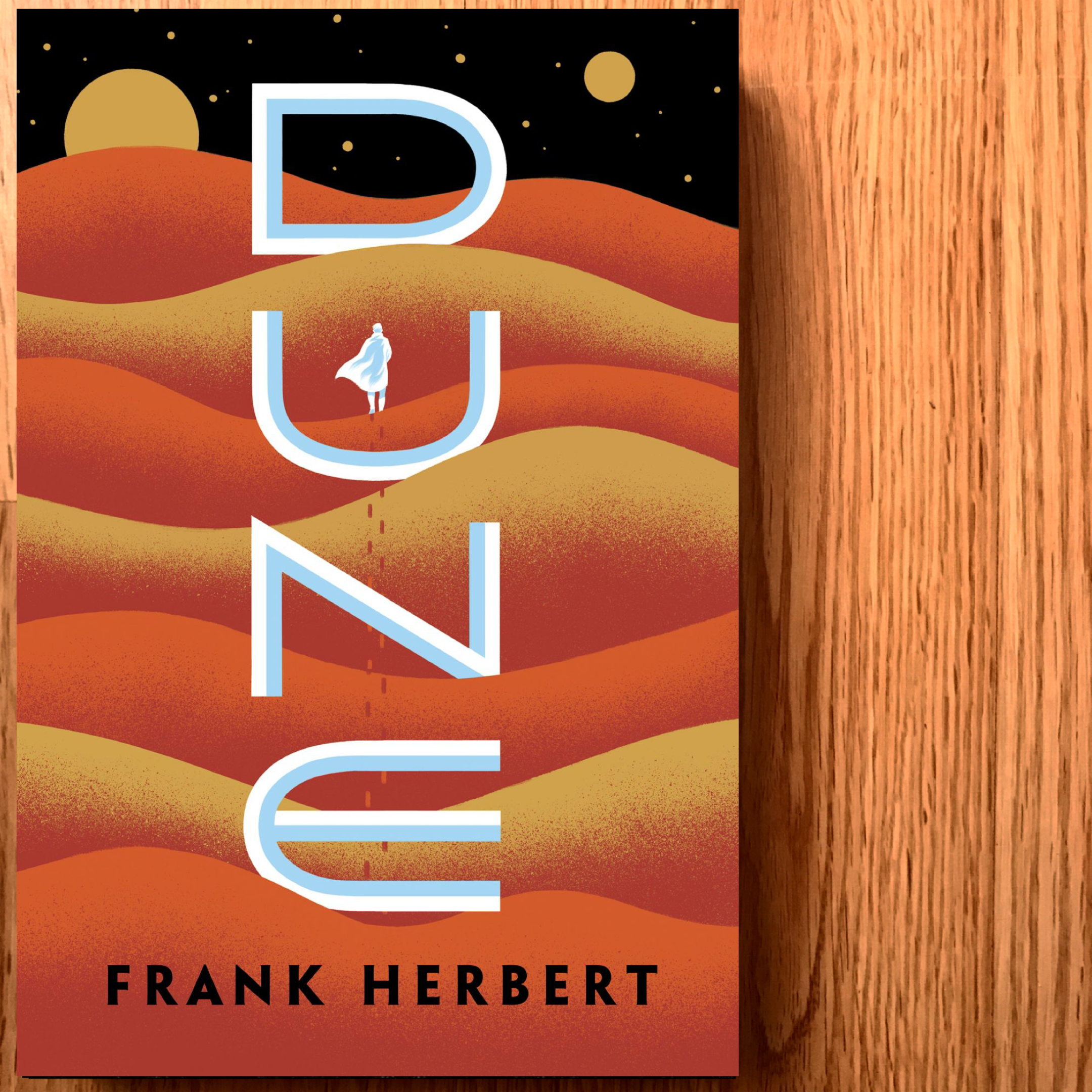

It wasn't the gushing praise I've heard from others when talking about Dune, but it nonetheless joined the other novels in my growing pile of reading material. It was that fat Berkley paperback edition that came out alongside the David Lynch film, the front cover consisting of two oddly coloured moons hanging over a desert while the back cover is filled with tiny hard-to-decipher stills from the film. In many ways it's a pretty terrible edition; it says little about the novel beyond its bestseller status, spending most of its energy trying to sell you the movie. That said, even at thirteen I knew a few things about my mother; one of these was that she didn't have it in her to recommend a bad book.

When I finally took the book in hand a few days later, I devoured it. Dune is a tremendous book, not just in terms of quality but also scale.

Dune is gloriously huge. It's obviously not a short book, but it's also a work of epic scope, an exercise in world-building that puts many others to shame. It was probably among the first books I read that really gave me the impression that the story was occurring in a fully realized universe. The desert planet of Arrakis is more than just a handful of locations and characters, and is itself shaped by - and reflects - an entire universe of intertwined power structures, political machinations, and religious influences. This is a world with rich and oft-misunderstood history that shapes its present; the background information is never just filler in Dune.

I don't know that Dune is for everybody, but for anybody even remotely interested in reading it I'd unreservedly suggest they do so. It is something to be experienced.